THE MEDIA ESCALATED THE SITUATION

August 26, 2022

INSTEAD OF OPPOSING INFORMATION CHAOS, SOME KOSOVO MEDIA OUTLETS CREATED IT

On June 29, 2022, the Kurti government took the decision to apply reciprocity measures against Serbia regarding personal identification documents. This meant that citizens of Serbia entering Kosovo, from August 1, would be provided with temporary forms replacing the documents issued by Serbia, a measure that has applied to citizens of Kosovo entering Serbia since 2011.

This decision caused a considerable reaction in the north of Kosovo. On the evening of July 29, groups of people blocked the border crossings at Jarinje and Brnjak with barricades and protests. A similar reaction occurred in September 2021, following the implementation of a measure requiring every vehicle with Serbian license plates entering Kosovo to replace the plates issued by Serbia with temporary ones — this too was an attempt to implement reciprocity measures with Serbia.

Kosovo and Serbia have continued the dialogue for the normalization of relations with mediation from the European Union (EU) since 2011. These blockades and protests are indicators that both countries have a long way to go towards normalization.

On the eve of the implementation of the decision regarding identification documents, Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić declared through the Russian agency Tass: “The situation for our people in Kosovo and Metohija is very difficult. We have never been in a more difficult position than today. The Prishtina regime is trying to use the situation in the world, as the new Zelensky, represented by Albin Kurti, declares war on hegemony. The actions to ban Serbian documents begins tonight at midnight.”

In response to the increasingly tense situation, the prime minister of Kosovo, Albin Kurti, and other state officials met with the American ambassador in Prishtina, Jeffrey Hovenier, who forwarded a request from the United States government to postpone the implementation of the measures for one month due to “misinformation, misunderstanding and disinformation regarding this decision.” The Kurti government pledged to postpone the implementation until September 1, 2022 and as a result, the barricades were withdrawn.

However, the time between July 31 and August 1 was enough for the incident to reach front-page headlines in local, regional media and beyond. The matter was widely addressed and written about from different perspectives. However, the news delivered to the public was often one-sided and unconfirmed.

NARRATIVES OF WAR AND CONFLICT

One of the initial articles produced in Kosovo after the formation of the barricades purported that a member of the Kosovo Police was injured while on duty in the north. This misinformation drew significant reactions from social media users.

Organizations that deal with fact-checking in Kosovo for Facebook soon evaluated this news as untrue. The Kosovo Police denied the news. Then Berat Buzhala, on behalf of Gazeta Nacionale, the online news outlet which had published the article in question, apologized for the mistake and for misreporting.

However, the general coverage of events nurtured narratives of conflict.

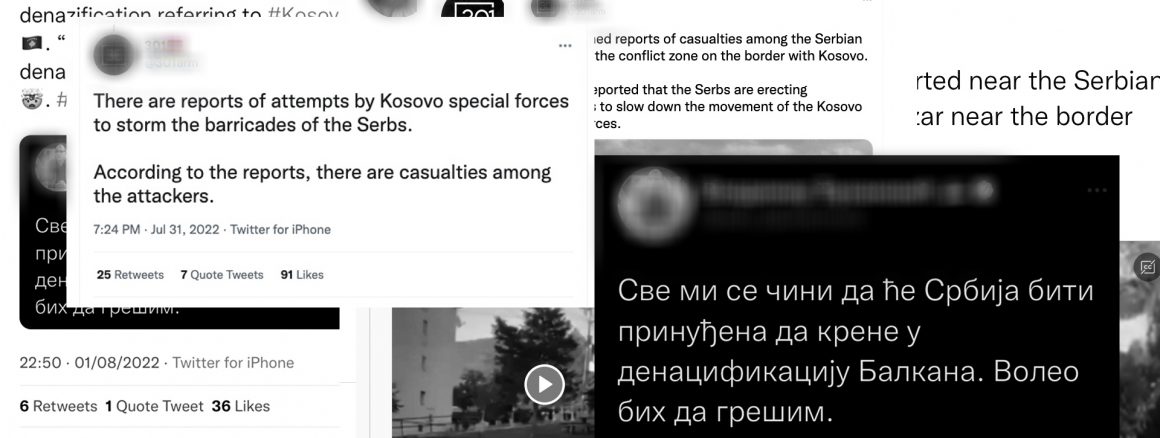

Many of those who compiled and spread this news focused more on predicting what might go wrong than on reporting the facts. As a result, the media atmosphere was influenced by unconfirmed information coming from posts on social media, in some cases made by anonymous accounts. Even journalists who reported on the scene often started their coverage by referring to this information.

Eyewitnesses are reliable sources for journalists, but they are not necessarily sources that reflect events as they happen. The eyewitnesses on the southern side of the barricades see the incident only from where they stand and therefore their perspective of events is limited, the same thing applies to eyewitnesses on the northern side.

By using posts on Twitter and Facebook as sources, journalists, in addition to over-simplifying the situation, “others” people and helps further deepen the narrative of “us” and “them.” Othering fuels conflict. By constructing a divide it denies the humanity of a person or group. Consequently, those who are seen as “others” are considered less worthy of dignity and respect.

Journalists in Kosovo should be familiar with covering these kinds of incidents. Since there have been several similar crises, journalists should be prepared to handle information with caution. Carelessness in such cases can lead to or facilitate further tensions, as happened in 2000 and 2004 in Kosovo.

The first instance is commonly known as the “Dita” case. In 2000, the newspaper Dita published the name, home address, photograph and work schedule of a Kosovo Serb, Petar Topoljski, and accused him of participating in war crimes. Two weeks after the publication, Topoljski was found murdered. As a result, the United Nations Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) shut down the newspaper. The investigations, despite having continued for years, have not resulted in the arrest of the perpetrators or a confirmation of the charges.

The second case occurred in March 2004, when after the tragic drowning of three Albanian children in the Ibar River, information was given to the public broadcasting network (RTK) by a child who had witnessed the incident. The child claimed that some local Serbs had attacked him with dogs, a claim which was never verified by journalists. In some of the coverage of this incident, journalists reported sensationally and carelessly. In the heated days that followed, massive anti-Serb riots broke out across the country.

A 2004 report by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) stated that if the reporting hadn’t included excessive emotion, prejudice, carelessness and “patriotic” duty, events might have taken another course. Adding that events might not have reached the same scale and level of brutality or might not have happened at all. Moreover, the accusations raised by the reporting have never been verified and no one has been held accountable.

Although this time the news of the police officer’s injury was quickly denied and the media apologized, the false claim spread fast and its presence on various platforms multiplied, increasing its opportunity to influence readers. Although there were no other consequences, it is important to consider how the two above cases demonstrate that misinformation can escalate the existing situation.

THE INFLUENCE OF SOCIAL MEDIA

Social networks played an essential role in shaping the reporting and understanding of the events of July 31 and August 1. Aside from the fact that these platforms served as a space to express support and to share information, they also became channels of political communication and a source for the media.

Twitter and Facebook became an essential source of information for both Kosovars and the international audience. In Kosovo, they became information platforms and spaces to express political support for the actions of the Kosovo Police. In fact, a whole campaign using photos of the Kosovo Police was launched as a sign of support for the Kurti government’s decision. Journalists also joined this campaign.

Some journalists in Kosovo, in addition to their usual role, took on the role of activists. Journalists began to openly support the actions of the police and this was also reflected in their reporting. As a result, unverified and biased news was spread to the public in Kosovo. Journalism in the entire Western Balkans is witness to this phenomenon.

In addition, political actors, such as representatives of the Russian and Serbian governments, used these platforms for political communication, further increasing the significance of social networks in the reporting of this event. The hashtag #Kosovo was used to comment on the events in Kosovo and then comparisons started to be made to the war in Ukraine.

Roughly 15 minutes after the reaction from the President of Serbia, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs made an announcement on the messenger application Telegram supporting Vučić’s narrative about the “injustice and persecution of the Serbian population in Kosovo.” The Kosovar government’s statements for international and local audiences claimed Russian influence in these events. Prime Minister Kurti reiterated this position in an interview for the Italian newspaper la Repubblica. These public claims of Russian involvement drew the attention of those concerned with the war in Ukraine

A sample of 10,000 tweets about the events in the north of Kosovo was gathered by Twitter for the two day duration of the crisis, July 31 and August 1, the sample was then analyzed with software for qualitative and quantitative analysis (MaxQDA). The research found that “Kosovo” was mentioned 8,935 times and the word “Ukraine” was mentioned 895 times. These findings show that in about 10% of the communication about these events, Ukraine was also mentioned. The word “Putin” was mentioned 780 times and “Kiev” 700 times.

It is interesting to consider the origins of these tweets. About 1,000 of the 10,000 tweets and retweets came from India, while the second highest number came from Ghana.

It seems suspicious that so many of the tweets about the events originated in India, Ghana, Italy and Spain. These likely bot farms are used to fabricate posts on Facebook and Twitter and they’re sophisticated; their locations can be shielded and encrypted through virtual private networks (VPN). Similarly, it seems suspicious that the reaction from the government of Serbia, including Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić and Minister of Interior Affairs Aleksandar Vulin, were closely followed by reactions from the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

These reactions on digital platforms were followed by posts and reposts from a host of users, but there was an anomaly in that about 25% of users were on computers and not smartphones, raising suspicions of an attempted influence campaign. It is much easier to operate multiple accounts on computers rather than mobile devices. With so many reactions on social media platforms, the topic trended for a while.

The “Twitter war” about the north of Kosovo created an excellent self-promotion opportunity for self-proclaimed “conflict experts.” Social media users who are active in commenting on the war in Ukraine, briefly turned their attention to the “war” in Kosovo. The media and social networks are a perfect environment for the cultivation of these supposed experts who make inflated claims about their sources or authority.

After a while, these “experts” strategically behave as such. In the case of Ukraine, such experts came into prominence around 2014, when the Russian Federation began annexing Crimea. When journalists quoted these sources about events in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine, many were mid-ranking government officials, and after eight years, they are seen as more reliable, having built up experience and a large network of collaborators.

Countless users from EU countries and elsewhere began to explain the problems in the north of Kosovo, equating it with eastern Ukraine and Russia with Serbia. The political leadership in Kosovo and Ukraine shared these sources of information, increasing their relevance.

The journalists who warned that the situation had “escalated” had no verified information. Many news stories in Kosovo were built on misconceptions about the events in the north of Kosovo based on the reports everyday people provided on digital platforms. This resulted in poor and biased coverage of events. While diversity of opinion is welcome, the media should be careful who and how they make use of quotes.

Nowadays, in a world facing information chaos and the increasing influence of information warfare, the objectivity of journalists’ information gathering methods is more important than ever. Journalists must equip themselves with specialized knowledge on how to verify images and texts from digital platforms in order to be better informed on propaganda strategies and deliberate misinformation from dubious sources. Accurate information must be a professional imperative.

Author: Abit Hoxha

Photo: Kosovo 2.0

This article was originally produced for and published by Kosovo 2.0 within the framework of RESILIENCE project. It has been re-published here with permission.