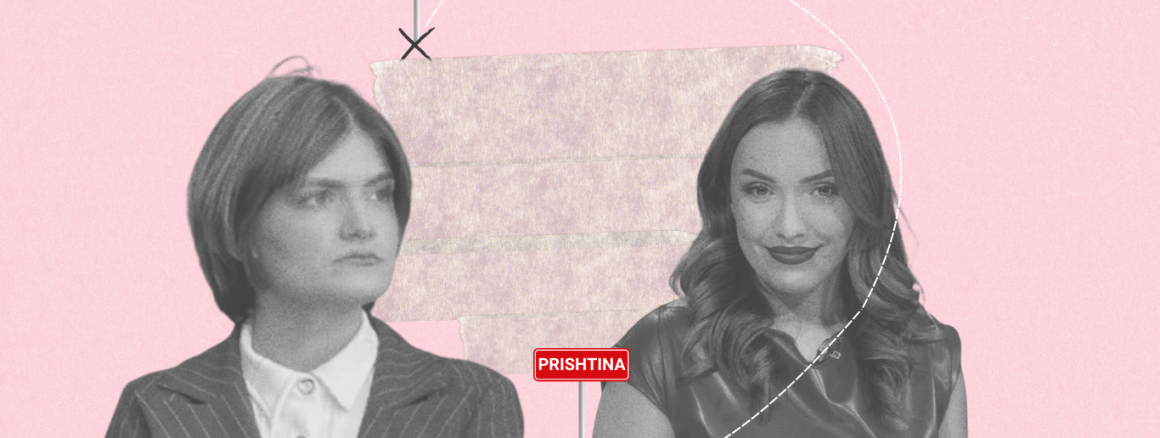

From Belgrade to Prishtina: Women Who Refused to Be Silent

December 10, 2025

On August 14, 2025, after one of many student protests in Belgrade, a group of students was attacked by the police while heading home and taken to a nearby garage. Among them was Nikolina Sinđelić, a survivor of police brutality.

“As we were walking down Nemanjina Street, we encountered members of the JZO (Unit for Protection of Certain Persons and Facilities), police officers, and several masked men whose identities were unknown to us,” Sinđelić said inan interview for N1.

According to her, men in plain clothes and balaclavas rushed out of a government building and began beating protesters with batons. The students claim they were forced to kneel with their hands behind their backs as the JZO commander, Marko Kričak, arrived. When he noticed a red light on Nikolina’s camera, he accused her of recording the violence, even though the camera had no batteries. All students had their phones immediately smashed, except Nikolina, whose phone was first confiscated and later returned completely destroyed. Her camera was seized as well.

Sinđelić spoke publicly about how Kričak physically assaulted her, threatening to strip and rape her in front of others. After the ordeal, all detained students were taken to the police station. Unfortunately, this was only the beginning of her story.

Less than four days after Sinđelić spoke publicly about police brutality and the actions of Marko Kričak, former State Secretary Dijana Hrkalović, convicted earlier this year for influence peddling, and the pro-government TV channel Informer published her intimate photos. The images were likely taken from her destroyed phone, in an attempt to discredit her. With REM (Regulatory Authority for Electronic Media) inactive and prosecutors silent, Nikolina’s only legal option was to file a private lawsuit.

A month later, the government introduced a draft law criminalising the misuse of intimate photos, videos, and recordings. Under current Serbian law, such cases are not prosecuted ex officio, forcing victims to initiate private lawsuits.

However, questions remain about how the new offence will be applied, given the judiciary’s dependence on the ruling party. Human rights organisations warn that women’s rights could once again be used for political gain rather than genuine protection.

Milena Vasić, attorney-at-law and program director at the Lawyers’ Committee for Human Rights (YUCOM), emphasised that introducing a new offence is meaningless without institutional capacity. “The capacities of the Office of the Prosecutor for High-Tech Crime, which should deal with it, also need to be strengthened. We have a very small number of prosecutors currently dealing with this specific type of criminal offence that falls under high-tech crime,“ she said.

Vasić added that the government is using women’s rights for populist purposes, while serious issues in the draft law remain unresolved.

Ana Zdravković from the organisation Osnažene told Zoomer.rs that one of the key issues with the draft law is the lack of clear definitions, particularly of what constitutes “sexually explicit content”, leaving room for inconsistent interpretations by courts. She also noted the absence of legal mechanisms for removing leaked content from the internet, meaning victims may remain exposed to violence even after court proceedings.

In the same Zoomer.rs interview, Vanja Macanović from the Autonomous Women’s Centre added that similar international acts, such as the UK’s Online Safety Act or the US Take It Down Act, often fail in practice because lawmakers do not understand how digital platforms function and rarely consult civil society experts.

Ultimately, Nikolina’s story reveals more than one case of police brutality. It exposes a system where perpetrators act with impunity, and victims are left to seek justice on their own. Without independent institutions and political will, the new law risks becoming another example of performative justice.

Her story is not an isolated incident but part of a broader regional pattern where speaking out, especially against gender-based violence, often comes at a cost. The mechanisms of impunity that protect perpetrators in Serbia are mirrored elsewhere in the Balkans, revealing a shared culture of silencing and intimidation. If you travel south from Belgrade to Prishtina, you’ll find a journalist who faced a strikingly similar fate for raising her voice, Ardiana Thaçi Mehmeti.

On the morning of Monday, May 7, 2024, Klan Kosova journalist Ardiana Thaçi Mehmeti faced a day unlike any other. Her phone flooded with messages and calls from unknown numbers, men demanding sexual favours, commenting on her appearance, asking her rates, and even sending nude photos.

This harassment began after her number was shared in the infamous AlbKings group, a notorious online community in Kosovo that circulated private information and targeted women with threats, blackmail, and exposure.

Only weeks earlier, Thaçi Mehmeti had reported on the group in her investigative show Kiks Kosova.

“The difference between this case and the other threats I have received is that this time I did not know who was behind it. In other cases of harassment and threats, I usually knew the person responsible and that it was connected to my work,” Thaçi Mehmeti explained.

“This time, there were around seventy thousand people involved, and when you go out on the street, you cannot identify who they are. That made it much more dangerous, especially because it was the first time someone attacked me based on gender and in a sexual way.”

The scale of the group’s reach was massive. According to a report by Balkan Insight in September of this year, the AlbKings group on Telegram had 120,000 members at its peak.

In response to the incident, the Association of Journalists of Kosovo (AJK) condemned the sharing of her phone number and the insulting messages and calls she received, stating that these actions aimed to damage her reputation.

“The publication of journalist Thaçi Mehmeti’s personal phone number as an act of revenge by AlbKings not only endangers her personal safety but also serves as an attempt to intimidate and silence her,” the AJK stated.

Despite public condemnation, the harassment against Thaçi Mehmeti escalated when group members sought contact information for her family.

For the first time, she questioned whether continuing her work was worth it, as the situation affected not only her but also her children, husband, and parents, especially her mother, who had undergone a mastectomy that January due to breast cancer.

“When my case happened, my mother saw it on television. The police, who had offered me close protection, were already at her house before I arrived. Seeing them and learning I was being targeted again, she feared I had been killed and had a panic attack that took two to three hours to calm.” she vividly remembers.

A nonchalant response leaves the victim without proper support

By February 9, 2024, Albkings had accumulated 20,993 photos and 19,516 videos. Shortly after that date, it switched to private mode. In May 2024, prosecutor Elza Bajrami explained that the group had previously been shut down but was later reopened on two separate occasions.

Ariana points out that public figures and ordinary women face very different experiences in seeking justice for harassment or abuse.

“When I went to report the case, the first thing a police officer told me was, “Just change your phone number.” I asked him, “Why should I? We live in the age of technology. If I change my number, everyone gets notified automatically.” – Thaçi Mehmeti explains.

“Besides, why should I give up something that belongs to me just because someone decided to harass me? If a police officer can say that to a journalist like me, what do they say to women who do not have a public voice?” she adds.

Another aspect of the issue appears to lie within Kosovo’s legal system.

In the second Albkings case, the prosecution removed Thaçi Mehmeti from the indictment, saying that she had not continued to communicate with the harassers.

“It felt strange to me because they were the ones harassing me. I had taken screenshots, blocked their numbers, and reported them. Even though two admitted to sending nude photos and asking for sexual favours, the prosecution argued the crime was not completed since I did not respond.” she says.

She adds that prosecutors often struggle to classify these cases and to apply the right punishments.

According to Thaçi Mehmeti, public trials, harsher punishments, and better-trained police are crucial to prevent harassment and ensure real accountability.

“The penalties are far too light. I wanted the trial to be public because I believed that when justice is transparent, others will think twice before committing the same acts. We fought for months to find and arrest those people.” she explains.

Once they were caught, I wanted them to face real punishment, not two months in prison or a fine of two thousand five hundred euros. When offenders are hidden or lightly punished, nothing changes.”

“Always report it. Reporting is power.”

Despite being targeted, insulted, and constantly subjected to intimidation and denigrating comments, Ardiana became the voice for many women who drew strength from her courage.

“Today, one of them has been convicted, while two others were released by the prosecution. I am happy that I became a voice for many women. When I went to court, I saw around twenty other women who had also been harassed by the same people, but they did not want their names revealed or their families to know.” she explains, adding that in the Balkans, traditional attitudes still treat women as shameful victims, even when they are the targets.

At the end of 2024, Ardiana Thaçi Mehmeti was awarded the Journalist of the Year 2024 by the Association of Journalists of Kosovo.

“By coincidence, I was added to a group called Albkings, and I dedicate this award to all those women who didn’t have other women to stand by them, who were forced to change their lives, their phone numbers, to stay silent, and not even tell their own families,” she said while receiving the award.

She also thanked the team of journalists from KIKS Kosova and expressed gratitude to her teenage children, who had a difficult time during this period due to bullying at school.

Today, looking back at the fear many women endure when their intimate photos are shared, Thaçi Mehmeti urges every woman to report such cases and not feel ashamed.

“You are not guilty because someone decided to harass or humiliate you because of your gender.” she says.

“Healing takes time, and I know how difficult it is, especially in a society where victims are often blamed. But we must keep our heads up and say, yes, this happened to me. We should not keep it a secret, and we should not isolate ourselves, because silence allows worse things to happen.” she concludes.

In both Belgrade and Prishtina, two women who dared to tell the truth found themselves punished for it. Their experiences reveal not only the gaps in the legal systems of these two societies but also the deep-rooted mindset that has cultivated a culture of silence, one where speaking up against injustice often comes at a cost, and where a woman’s morality is placed under scrutiny by the very society that claims to define what is moral and what is not.

Yet, the stories of these two women carry a glimmer of hope, showing that resistance begins when someone dares to speak, and that change, however slow, is born from that first act of defiance. Nikolina and Ardiana remind us that raising one’s voice is not only an act of courage but also a way of reclaiming dignity, truth, and the right to be heard.

Authors: Bubulina Peni & Ana Adžić