Author: Ivana Jelača

WHEN THE MEDIA USE TERRORIST TROPES: The Coverage of Dine Hoxha Attack in Albania

May 28, 2021

On 19 April 2021, a young man entered the “Dine Hoxha” mosque in Tirana, the capital of Albania, and injured five people by stabbing them. According to testimonies by his family members, the man used to attend prayers in the mosque frequently after he had converted to Islam. During the coverage of the incident by the country’s media, it was mentioned that the man had mental health issues, he was hospitalised several times in a psychiatric hospital and he was receiving medication. In an interview, the man’s father mentioned that his son was concerned of his life as he thought that a group of people was following him and wanted to kill him. In addition to that, the media reported that the man had self-isolated after contracting COVID-19 which could have worsened his mental health.

Albania is known for its religious harmony and incidents of this kind in worship spaces have never happened before. Thus, the media’s interest in covering it from the scene was high. However, the coverage of this case, which was immediately characterised as a terrorist attack, was flawed and a lack of professionalism was noticeable. The majority of the country’s media rushed to cover the case under the ‘terrorist lens’ without having any evidence or information that it was such an attack. In their attempt to be the first who cover the event, some journalists forgot one of journalism’s main rules: accuracy.

As the news developed sensationalist headlines took over:

“Catholic terrorist”, “accused of a terrorist act”, “… slaughtering believers in the mosque”, “Catholic is 7 times worse than ‘shkjau’”, “the attack may have started from “religious extremism”, “… attacked the believer who read the Qur’an”, “the attack takes place in the holy month for Muslims”, “Muslims should be punished”, etc.

Event such as this should be reported immediately due to their seriousness, however, journalists have a responsibility to their audience and to the general public. Such headlines and comments can mislead and misinform the general public and essentially lead to religious hatred. The media’s role is to inform the public based on facts and not to incite verbal violence and/or hatred against various religious groups in society, with unprofessional, irresponsible and inaccurate reporting. A journalist’s responsibility is even higher when it comes to such complex incidents, which combine reporting on mental health and religion.

In this case, journalists and the media should refer to the media’s Code of Ethics as well as to the country’s relevant legislation in order to inform the public correctly. Journalists should always make clear the cases when the information is not confirmed, so as not to mislead the public. The media should also make a clear distinction between an opinion and fact. During the “Dine Hoxha” case the Albanian media failed to report accurately and their coverage was clearly based on bias and opinions.

It is the media’s professional and legal obligation to not “present material that incites hatred or violence against individuals on the basis of race, religion, nationality, colour, ethnic origin, membership, gender, sexual orientation, civil status, disability, illness or age” as stated in the Code of Ethics, article 8.

Author: Dorentina Hysa

Photo credit: Don Pablo/ Shutterstock

“HATE SLAVS” – HATE SPEECH IN THE BALKANS

May 28, 2021

Hate speech is commonplace in public discourse in the Balkans

Offensive language, insinuations, labelling, presenting false information about people in public discourse with no holds barred, whether it is the media or the assembly i.e., in public debates, or in messages on social media and other public platforms, has become more the norm than an exception in the Western. Balkans.

Despite the existence of both codes of ethics and legal protection, hate speech is a part of everyday life, it is shared in public without a second thought. This blog is dedicated to our “non-accountability” to what is said in public discourse. “Got killed by the harshest of words” (Ubi me prejaka reč) was a line in a song sung a long time ago by Branko Miljković, as well as many others who became victims of “hate speech” in public communication and never managed to get rid of the burden of the spoken insults, lies, labelling. Even when they would prove that they are right in court, as a rule, public opinion never stands to correct them. So, it is not a matter of penalizing “hate speech” but preventing it. This is one of the very important tasks of media literacy of young people and the citizen at large.

Code(s) of Journalists

The first level of protection against hate speech when it comes to the media, be it traditional or digital media, are the so-called professional codes of ethics. In the Code of Journalists of Serbia, hate speech is mentioned only in Chapter IV “Accountability of Journalists”:

“1. The journalist is, above all, accountable to his readers, listeners and viewers. That accountability must not be subordinated to the interests of others, and especially to the interests of publicists, the government and other state bodies. A journalist must oppose anyone who violates human rights or advocates any kind of discrimination, hate speech and incitement to violence.” Guideline 3 adds “Colloquial, derogatory and imprecise naming of a certain group is inadmissible.”

The Code of Journalists of Montenegro defines “hate speech” in much more detail on page 13 in the Guidelines for Principle 4 under 1.4 “Hate speech”, stating:

“(a) The media may not publish material intended to spread hostility or hatred towards persons because of their race, ethnicity, nationality, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, physical and mental condition or illness, as well as political affiliation. The same is true if there is a high probability that publishing some material would provoke the aforementioned hostility and hatred. (b) The journalist must avoid publishing details and derogatory qualifications about race, colour, ethnicity, nationality, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, physical and mental condition or illness, family status, and political affiliation, except if it is in the public interest. (c) A journalist must take special precautions not to contribute to the spread of hatred when reporting on events and phenomena that contain elements of hatred. It is the journalist’s obligation to respect other states and nations.”

In the Code of Honour of Croatian Journalists, item 13 “Fundamental Human Rights and Freedoms” states that,

“In the line of their work, journalists shall respect, protect and promote fundamental human rights and freedoms, and in particular the principle of equality of all citizens. Special accountability is expected when reporting or providing commentary on the rights, needs, problems and demands of minority societal groups. Information on race, colour, religion or nationality, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender expression, any physical or mental characteristics or disease, marital status, lifestyle, social status, financial standing or level of education shall be provided by the journalist only if it is extremely relevant to the context in which it is presented. It is inadmissible to use stereotypes, pejorative terms, debasing portrayal, as well as any other form of direct or indirect incitement or support of discrimination.”

This is the case in all other professional codes of ethics in the countries of the Western Balkans, as well as in the world, as they are based on the elementary document of this type, the so-called “Munich Declaration” from 1971. Namely, the representatives of the journalists’ trade union of six member states of the European Community adopted the “Declaration on the Rights and Obligations of Journalists of the European Community” (Lorimer, 1998, 156-158) on the basis of which many national associations of journalists and some media houses later on created their own internal codes of behaviour. Of course, the phrase “hate speech” came into public use many decades later, but the model was recognized in this document, made exactly half a century ago.

The legislation of all countries recognizes the concept of “insult” and it is a very controversial and sensitive “tort”. We will therefore quote the explanation of a very famous judge from Serbia, Miša Majić:

“When it comes to the crime of insult, things are not as simple as it may sometimes seem. What constitutes conflicting views in case law is contained in paragraph 4 of Art. 170 of the Criminal Code. Namely, it is stated here, among other things, that the perpetrator shall not be punished for an act of insult if the statement is given as part of serious criticism in a scientific, literary or artistic work, in performing official duties, the journalistic profession, political activity, defending a right or protecting legitimate interests, if it is clear from the manner of expression or from other circumstances that this was not done with the intention of belittling. Thus, the court that would have to assess, taking into consideration all the circumstances of the case, whether the statement, which is purely objectively seen as offensive (the plaintiff is a “liar”), was given in this case in defence of some rights or protection of legitimate interests, and whether the manner of expression and other circumstances indicate that this was not done with the intention of belittling. Therefore, both of these elements (circumstances + intentions) would have to be present.”

Since this “general place” can also be found in all court practices throughout the Balkans, we believe that we have resolved the basic dilemmas about whether hate speech has been “processed” in ethical and legislative practice. Yet, why is “hate speech” still very much present in public discourse and how do we curb it? The answer to these questions is not at all simple. One possible solution was given in an advocacy video of the NGO Buka from Sarajevo, which got millions of views in just a few days.

Creative indication of “excessiveness”

Here is just a part of the dialogue of this video, as an example of general non-accountability in the vocabulary choices we witness every day:

“Give me a veal shank, you fat pig.

– Will this one-pounder do, or would you like two pounds, you Turkish whore?

– One pound is fine, you Chetnik fagot.”

Marija Janković, a BBC journalist, wrote the article “Hate Slavs and the Balkans: How the Yugoslav Anthem Inspired the Fight Against Hate Speech”, on April 12, 2021. The article quotes Aleksandar Trifunović, director of Buka: “The initial inspiration for the video was the song Hey, Slavs, which was the anthem of former Yugoslavia for almost half a century”, adding: “This time we decided to fight hate speech just like the vaccines fight coronavirus – you have to put a piece of the virus in the vaccine to kill the virus. So, we had to insert a piece of hate speech to fight it.”

It seems that the video really is one of the possible solutions against hate speech, because it was broadcast on the Internet, which is a communication channel that young people prefer, so it is most likely to reach the target group online and try and make them aware and help them learn how to recognize “hate speech” and how to stand up against it. It showed, in a creative and sarcastic way, how we have completely lost our sense of etiquette, decency and communication in public speech, the goal of which should be dialogue and debate, and not insulting and belittling anyone around us who might be different.

This did not happen overnight

In essence, it all started thirty years ago, when newspaper articles in the media on the territory of the entire former Yugoslavia “fired from all available linguistic means” or as our famous sociolinguist Professor Ranko Bugarski PhD said in his book “Language from Peace to War” – it was words that were fired first on the territory of former Yugoslavia, the cannons came after. Let us also recall the war reporting of the 1990s. When the media reported from the battlefield, each side in the conflict called the other in the most derogatory words and expressions, which were dug up from vocabulary used in the past, such as “Ustasha”, “Chetnik”, “Balija” to much more ominous ones, such as “Alija’s rapists and haters”, referring to politician Alija Izetbegovic who was the leader of Bosnian Muslims or Bosniaks as they later identified themselves.

So, what the media industry started then continues today and is exacerbated by the potential provided by new digital technologies, allowing users themselves to comment on texts posted in online editions of traditional media or on new media portals, or to speak their mind on social media. The very possibility of being anonymous and the absence of a clear boundary between the private and the public in the online sphere has contributed to the fact that many have forgotten about civility in communication.

“Street slang and curse words have become commonplace in public communication, in parliament, in political life in general. The reason for this is not the lack of linguistic or political culture, but a deliberate policy of verbal violence” (Ranko Bugarski, NIN, 19.11.2020, page 20). It is about exerting power through linguistic choices, which political ruling elites practice on a daily basis in communication with journalists, the public, and politicians.

The model of public communication they have established is also becoming the model of “best” practice for others, a pattern according to which anything goes, regardless of whether it crosses the boundaries of basic decency and enters the area of open verbal violence. If the statements of Members of Parliament are not sanctioned, like the one of Voislav Šešelj, which is one of the countless examples of hate speech spoken behind the rostrum of the most democratic body of every society, then it is impossible to expect different models of communication to be present in public discourse in other spheres: “You know, you have heard of Snezana Chongradin, she is very ugly, uglier even than Stasa Zajovic. Stasa Zajovic is a catch compared to her. She looks like a mongoose. A real mongoose, I swear on my life. Can you imagine that Snezana Chongradin, who looks like a mongoose, wrote…”.

And what does the online community write?

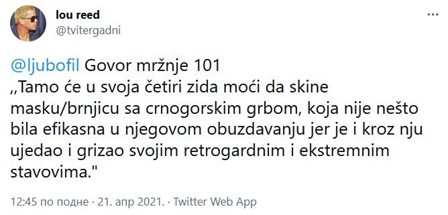

No one gets worked-up anymore about the statements coming from the parliamentary rostrum that insult all those who are not us, because they have become part of the daily “parliamentary repertoire” and the fight “for a better tomorrow”. The online community cares even less about etiquette in public discourse. Such posts on Twitter are part of the daily offer of hate speech and expression of intolerance towards people with different opinions, even when they condemn hate speech:

“There, within his four walls, he’ll be able to take off his mask bearing the Montenegrin Coat of Arms, which really did not help to contain him, for he bit and chewed through it with his retrograde and extremist opinions.”

On April 21 1991, an All-Serb rally was organized in the village of Jagodnjak in Baranja county. The Serbian MP Milan Paroshki spewed terrible hate speech, telling the Serbs who live there: “You can kill whoever says that this is not Serbian, as if they were a dog near the fence”.

Where would Marina use hate speech? Lying dogs! She is known for being a tolerant and peace-loving MP. Until she puts on animal-print high heels and gets her hands on a bottle or a fire cracker!

Is there a pattern that is followed without a second thought?

Hate speech has clear patterns at the explicit and the implicit level i.e., concerning both content and form. The content is easily recognizable, chiefly through the vocabulary that is obscene and obscure and not appropriate for public speech, but it is also easiest to identify and if there is a desire, it can be easily excluded from public communication by simply moderating user comments on a news portal, filtering out such content. Actually, anyone who does not want their “personal space” to be polluted, they can block people who spread hate speech on Twitter or unfriend them on Facebook. For the most part, lexical aggression is absent in traditional media, with the exception of tabloids.

According to the research of CEPROM “Communicative aggression in Serbia 2019”, aggressive communication is six times more present in the online sphere compared to print media, because as many as 86 percent (17,169 texts) of problematic texts containing hate speech, sensationalism and aggression were published on news portals, while 14 percent (2 795 texts) were published in the daily press.”

The situation is much more complicated with narratives and discourse strategies that implicitly spread hatred and intolerance towards those who do not belong in one’s group or have a different opinion, in both traditional and new media. In order to deconstruct discourse strategies, we still need a scientific apparatus, and therefore researchers have a big and serious task to analyse the public speech of “symbolic elites” (a term of Teun A. van Dijk) in the Western Balkans, which have contributed to communicative pollution of public space. Journalists, writers, publicists, directors, actors, and other representatives of the creative industry are considered to be part of the symbolic elites, because they are the ones who can subtly mediate hate speech on behalf of the political ruling power in a way that is not clearly identifiable and therefore the audience’s defence mechanisms are not prepared and often do not react at all.

There are countless examples, especially in the media. It is enough to convey the words of participants in events that spread hate speech without adding any comment, or to publicise an event that does not deserve it, because it is not significant enough to be considered “of public interest” i.e., that certain subjects of social practice are never quoted directly in the media because they do not belong to ruling elites, and others dominate TV air-time with public appearances because they have the power in society to speak whenever and wherever they wish, whatever the occasion and whatever is on their mind. For example, in 14 analysed editions of the prime-time television news of the Serbian public broadcasting service, Aleksandar Vučić was quoted 28 times, on average twice per edition.

If a certain social group is always portrayed in a negative context, regardless of its actual public appearances, actions, or inactions, that also constitutes hate speech, which is always the case when it comes to opposition leaders in the Western Balkans. Contrary to this, the statements of young leaders of the ruling party are ever-so-present in the media, and they use every opportunity in the Assembly to speak negatively about the opposition, which, by the way, is not even present in the national parliament. Whatever the topic, it is only important to mention the opposition in a negative context, because firstly, the sessions are broadcast live, and secondly, the media and social media cite it abundantly later on, making the popularity grow: Luka Kebara “Just look at how former tycoon politicians like Mr. Dragan Đilas or Mrs. Marinika Čobanov-živka-morović Tepić, they were among the first to say that the vaccine was not good, that our state was not able to procure those vaccines, and they were among the first to run and get a jab of that vaccine at the first chance they got. And they received vaccines from various producers, members of their party, that banana-party, freedom, justice, whatever its name is, an irrelevant party”.

Who are the best target practices for hate speech?

In the Western Balkans, they are always the same subjects, those who do not possess any social power, being a convenient group to be subject of attack so as to divert the public’s attention from much more important topics, such as various wrongdoings of those who have that power. So, in addition to the opposition, there are also migrants, journalists who criticise the government, marginalized groups, national minorities, and the LGBT population.

The media have power and use it extensively in the Western Balkans to produce and spread “moral panic” and further marginalize societal groups by condemning them with the abundant use of hate speech, as symptoms and causes of wider social tensions and immorality of all kinds, be it disinformation, manipulative content or fake news.

The patterns are always the same, and these specific examples are only nuances of the manifestation.

Author: Dubravka Valić Nedeljković, PhD

The artickle was first pubnished in ResPublica, where you can read it in Albanian, Macedonian and Bosnian/Montenegrin/Serbian.

Photo credit: Andrii Yalanskyi/ Shutterstock

HATE SPEECH IN THE WESTERN BALKANS: Monthly Monitoring Highlights

May 13, 2021

Throughout April, RDN monitoring team has detected diverse type of hateful narratives. This month we will have a country spotlight including five Western Balkans countries.

Roma in North Macedonia: Hate speech from high school teacher on International Roma Day

A teacher at the economic high school in Tetovo made offensive comments on her Facebook account towards the Roma community during the International Roma Day. In her post, she stated that she does not understand why Roma people are celebrated, and she further humiliated them by saying that they are lazy and that they want everything given to them without investing any effort.

“I do not understand why you feel so sorry for the Roma. There are some of them in my neighborhood and I know them very well. If they had a little more power, they would make us – Albanians – disappear. […] Nobody forbids their education; they do not want to work and they want everything given to them on a plate.”

The fact that a high school teacher and a member of the educational community in North Macedonia made such comments hurts public discourse in the country and encourages hate speech towards the Roma community. Additionally, as an authority figure among the students, the teacher might incite and perpetuate further hate among younger generations of non-Roma students, as well as make Roma students feel even more marginalized than they already are.

In addition to this case, the media in North Macedonia recently highlighted some very stereotypical and dangerous definitions of ‘Roma’ in high school textbooks. Roma people are referred to as “mainly uneducated” and those who “reproduce in old, traditional ways” calling for measures to control birth rates within the Roma community.

Roma in Albania: Derogatory terminology and analogies to chaos and disorganized political and social context

During a prime-time TV show in which COVID-19 vaccines were discussed, journalist Enton Abilekaj, used the pejorative term “gypsies”, which is offensive towards the representatives of the Roma community in the local Albanian context. During this incident, Enton Abilekaj was not targeting Roma people themselves, however, by using the term “gypsies” to refer to chaotic and disorganised practices he perpetuated an offensive stereotype and made harm created bad ideas about the Roma.

Olsi Sherifi, a Roma journalist, reacted to this by drawing attention and writing an informative article about the Roma community in the country in which he also mentioned the legal context. Reporting Diversity Network 2.0 partner in Albania- Albanian Media Institute highlights that it is a good practice that a Roma journalist acted and reacted on this incident. The reaction from a community member is most suitable and, in terms of the media, it is important to give platform to the voices of Roma professionals.

On 8 April 2021, Reporting Diversity Network 2.0 marked the International Roma Day in which the underrepresentation of Roma people in the media was highlighted as a concerning trend in all Western Balkan countries, including Albania. By giving the spotlight to Roma community members and associating them with negative stereotypes only further perpetuates the marginalization of the community in the media and the society.

Sexism in Kosovo: Basketball player, Milica Dabovic, subjected to sexist and nationalist speech for signing a contract with basketball club in Tirana

When basketball player Milica Dabovic announced on her Instagram profile that she had signed an agreement with a basketball team in Tirana, the web portal Kosovo Online which operates in the north of Kosovo, republished the news. Dabovic wrote on Instagram:

“New life, new goal, what a feeling! Finally my dream come true. I waited for so long. Thank you!”

Kosovo Online’s republication of the news on their portal and later on their social media, caused Facebook users to use hate speech on the Facebook post’s comments. Commenters used the words “bitch”, “cow” and other derogatory names for Milica Dabovic.

Tangible tensions between Serbians and Albanians in Kosovo are obvious in most of the comments. In this particular context, basketball player Dabovic is being attacked for saying that her dream came true by getting a chance to play for a Tirana based club. For this, she faced numerous verbal attacks on social media. Among other names, she was called a traitor of her own nation.

Homophobia in Serbia: Homophobic hate speech on Serbia’s national broadcaster’s TV show “Happy”

Two guests of TV Happy’s morning show who are public figures in Serbia -Miroljub Petrovic and Dragoslav Bokan – discussed the potential adoption of the Law on Same-Sex partnerships and LGBTQ+ rights. Petrovic and Bokan had several quite problematic statements that are considered hate speech and can even cause harm to the safety of the LGBTQ+ community in Serbia.

In their appearance Petrovic and Bokan also used some conspiracy theories. They said:

“The gay lobby controls finances in the world and the fastest way to get a job is not to finish school or college, but to become part of the LGBT population. And then you get a job fast”.

In addition:

“The Gay Parade has nothing to do with homosexuals, it has to do only with people who want to destroy Serbia. Homosexuals are victims, they are Trojan horse”.

These narratives that claim that the fight for equality of LGBTQ+ community is driven by an external agenda only removes the focus from the real problems and challenges that these marginalised communities deal with.

Moreover the comment “[a]ccording to the Bible, the death penalty is prescribed for homosexualism” can potentially incite violence.

All this happened on a TV show that was broadcasted on a television with national frequency, it was afterwards shared on TV Happy Morning show YouTube channel and had around 34056 views.

Media Diversity Institute Western Balkans, has had a public reaction that pointed out that this kind of speech is homophobia as well as pointed out at lack of reaction of both hosts and Regulatory Authority.

Bosnia and Herzegovina: Hate speech towards journalist Nidzara Ahmetasevic and migrant and refugee communities

In Bosnia and Herzegovina there were several incidents related to anti-migrant narratives which intersect with other incidents towards women and women journalists. The hate speech that comes from the website antimigrant.ba is not new to RDN monitoring team who selected this web platform as Balkan Troll of the Month earlier this year for spreading harmful and hateful rhetoric towards the migrant and refugee communities in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Namely, this same website used derogatory characterizations towards journalist Nidzara Ahmetasevic, who was previously targeted by police brutality. The web portal named Ahmetasevic a ‘’pro-migrant mafia’’. They also targeted the Facebook account of a solidarity platform Trans-Balkan solidarity and named them Transsexual solidarity and labeled them as pro-migrant mafia by alleging that they accuse citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina for spreading COVID-19 towards the migrant communities.

The web portal antimigrant.ba has been reported to the local Press Council for numerous incidents related to hate speech.

BALKAN TROLL OF THE MONTH: Tahir Batatini, Kosovo Football Coach

May 4, 2021

The Balkan Troll of the Month is an individual, a group of individuals or a media outlet that spreads hate on the internet based on gender, ethnicity, religion, or other diversity categories. The Balkan Troll is selected based on hate speech incidents identified across the Western Balkans region.

Our April Troll is Kosovo football coach Tahir Batatini who showcased sexist behavior on national television in Kosovo towards female journalist Qendresa Krelani.

The incident occurred during the TV show “Sport Total“ on TV Koha Vizioni KTV. The journalist Qendresa Krelani asked Tahir Batatini, football coach of the club Lap: “Mr.Batatini, when you have results such as yours all the time, what are your aims? Batatini answered: “In journalism, you can stack newspapers, or clean something, but not analyse football in this way”. Batatini also added: “Your level is not that of a journalist, starting from your appearance”.

Despite the fact that so far there were no statements such as this one, society in Kosovo is still predominantly patriarchal. Although there are women in sport journalism are , it is still perceived mainly as a male profession. Social media comments related to this incident confirm this.

Just few days after the sexist comments by Tahir Batatini, another sexist and homophobic incident happened, involving Kosovo Imam Shefqet Krasniqi who also appeared on national television to share his views on gender role divisions and other patriarchal viewpoints.

Kosovo 2.0 and Reporting Diversity Network 2.0 article “We Are Barely Scratching the Surface of Sexism in the Media“ by Dafina Halili gave an overview of both incidents while challenging sexism in Kosovar media and the lack of reaction by media organisations more generally.

“One has to be a football expert in order to assess the words of the sports journalist, but Batatina didn’t patronize her for her lack of expertise but for her gender, just as Krasniqi does with all women,” writes Halili, and continues: “Furthermore the hegemonic masculinity of sports and religion traditionally sees women sports journalists, or any women, as unwanted newcomers in the male realm who should have stayed in the kitchen. And the media reproduces exactly that deformed reality within a patriarchal ideology. How media organizations participate in the culture of oppression is best seen through the immediate reaction — or lack of it — from journalists, editors and media owners toward the sexism by Batatina and Krasniqi. One might expect their comments to instantly backfire, but there was minimal reaction from journalists in the studio, or their superiors. “

Marking the World Press Freedom Day, Reporting Diversity Network 2.0 put the spotlight on the diverse challenges that women journalists face in the Western Balkans. The campaign shared the daily struggles and efforts of women journalists from Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia; from not being treated equally to their male counterparts to being target of sexism comments, threats or brutal campaigns. Women who report on corruption and abuse of power or who try to promote the minority rights tend to face more challenges.

Ahead of World Press Freedom Day, the report “The Chilling: Global trends in online violence against women journalists“ was published and revealed striking findings related to online violence and hate directed towards women journalist. The report is based on a global survey of 901 journalists from 125 countries conducted in five languages; long-form interviews with 173 international journalists, editors, and experts in the fields of freedom of expression, human rights law, and digital safety and two big data case studies assessing over 2.5 million posts on Facebook and Twitter.

The research identifies some worrisome trends, reflected in the findings such as that 64% of all white women journalists surveyed said they had experienced online violence, the rates were higher for those identifying as Black (81%), Indigenous (86%), and Jewish (88%). Similar is found for lesbian and bisexual journalists, where 88% and 85%, respectively, have declared they face online abuse compared to 72% of heterosexual women.

Read the full report published by the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) and under commission from The United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) here.

HATE SPEECH DURING THE ELECTION CAMPAIGN IN ALBANIA

April 26, 2021

On 25 April, Albania had its parliamentary elections and the current Prime Minister, Edi Rama is set to win as preliminary results show. However, the focus of this article is not the political environment or the results of the elections but what happened during the electoral campaign. By looking at the rhetoric of all sides it is clearer than ever that the electoral campaign was dominated by hate speech. Political hate speech remains one of the most prominent forms of hate speech, particularly during electoral campaigns.

During March, Reporting Diversity Network 2.0 identified several hate speech incidents, which were perpetrated by key political figures in the country. In this article we will refer to the main incidents that drew the attention of the public and the media, and at the same time are important to be addressed. Incidents include the use of hate speech, offensive, derogatory and sexist language, which various political figures used against each other.

The most debated incident of this period was the one that involved the Prime Minister of the country, Edi Rama and the candidate for MP of the Democratic Party, Grida Duma, who have attracted public attention for the use of inappropriate language against each other. More specifically, it has been noted that the Prime Minister, during a direct presentation of his political candidates who will run in the parliamentary elections, introduced them compared to the candidates coming from the opposition party (PD). The photos of the opposition candidates were derogatory, out of context and with sexist content. Particular attention was drawn to the photo he used to represent Grida Duma, which he accompanied with the description “Gridare, Gridare, Gridare ooooo”, which significantly adds sexist tones to the selected image.

On the other hand, reactions with the same language came from representatives of other political parties in the country, such as Grida Duma, who in a post on her FB page shared videos with insulting calls to the Prime Minister. Also, Nora Malaj MP of the SMI in parliament has reacted regarding the Rama-Duma incident, using aggressive contemptuous language (sick, injured hyena, etc.). On the other hand, it is noted the use of hate speech language against various representatives of civil society, pointing the finger on those who did not react to the incident.

A response to the incident came in the form of a public call from 24 civil society organizations, which called for the ban on the use of hate speech against women in politics. Their call was addressed to political entities, the media, as well as the Commissioner for Protection from Discrimination.

This incident in particular, but also the massive use of hate speech during the election campaign prompted the reaction of the Head of the European Union Delegation in Tirana, Luigi Soreca, who in a public statement recalled the “importance of constructive and comprehensive political dialogue…that is based on mutual respect, dialogue and restraint, and is conducted in a peaceful manner, without provocative rhetoric or hate speech. ” In the same line with the EU delegation stand the recommendations of the Commissioner for Protection from Discrimination and the Central Election Commission, which in particular emphasize the “prevention of hate speech during the election campaign”, both by political parties and their supporters, as well as by the media which “should refuse to cover election campaigns that use or support hate speech.”

It is worth noting that, even when the media and journalists do not directly use hate speech in what they publish, they amplify the hate speech that politicians use by reporting on those incident and constantly repeating their narratives in violation of the Code of Ethics. Reporting and coverage of these incidents by media professionals should be done responsibly, accompanied by the necessary explanations and critical reflections on the context, in order to contribute to reducing hate speech, not spreading and increasing it.

Author: Dorentina Hysa

Photo credit: Andrij Vatsyk/ Shutterstock

WE ARE BARELY SCRATCHING THE SURFACE OF SEXISM IN THE MEDIA

April 21, 2021

THREE HIGH PROFILE INCIDENTS IN A WEEK ARE PART OF A DEEPER-ROOTED PROBLEM.

Three men walk into a bar: A sports trainer, a religious leader and a media owner, reads the script. With pretentious smiles and flamboyant steps they make their way to a free table.

The waiter approaches them and asks what they would like to drink.

They notice the bar has the drink from the TV ad that features the text: “For men, not for boys.”

“Shweppes,” they answer uniformly.

The waiter brings them the requested beverage and with straws in their mouths they look around and move their heads to the rhythm of the background music. Soon, they begin a coordinated lip sync, half whispering a verse of a song by the hip-hop trio Lyrical Son, Mc Kresha dhe Ledri Vula:

Ti menon që munesh ndamas (You think you can make it on your own)

Po s’munesh as tanga me ble pa mu (But you cannot even buy your underwear)

Le mo Louis e ksi gjana (Let alone Louis [Vuitton] and such things)

Për ty janë tema t’randa me i bo (They are heavy topics for you)

Their attention to the music is interrupted by laughter from a group of three women on the table opposite them. The three men try to make eye contact, but their attempts to flirt are ignored.

Unperturbed, they make a second attempt to get attention, shouting some inexplicable words, Johnny Bravo style. Still, they are completely ignored by the three women.

Suddenly the sports trainer says: “These women are only good for stacking empty bottles and cleaning things in the kitchen.”

The religious leader nods his approval: “You’re totally right, dude! A woman’s place is in the kitchen.”

The media owner raises his eyebrows and smiles:

“Come on guys, don’t be like that. I can find prettier women than them and bring them as a gift to you at this table.”

The script ends with a note: Based on true events, inspired by the Albanian language media.

* * *

The scene painted above might seem like some kind of cheap joke. But it is far too close to everyday reality to be funny.

In recent days, three prominent names — football coach, Tahir Batatina, one of the leaders of Kosovo’s Muslim community, Shefqet Krasniqi, and media veteran Baton Haxhiu — have become the latest protagonists of blatant, deliberate, misogynistic slurs, with two of them taking place on prime time TV.

The reactions of some individual journalists, activists and other citizens have ensured their words have been met with a fierce backlash. Many have also criticized the media moderators, journalists and owners for enabling the space to guests such as Krasniqi, who is known for spreading gender intolerance and sexist remarks.

But, even if all media outlets took editorial decisions to never again invite men into their studios who had previously contributed to misogynistic narratives in the press toward women, it would only scratch the surface of a deeply rooted problem: The power of patriarchy in the heart of media culture.

Prime time discrimination

Let’s look at the real TV script from the past week.

On April 11, on KTV sports show “Sporti Total,” the RTK journalist Qendresa Krelani criticized football manager and current coach of Llapi, Batatina, suggesting that supporters had lost trust in him as a coach and asking where he was heading with his team’s recent poor results.

“In journalism, you can stack newspapers, or clean something, but not analyze football in this way,” Batatina replied. “Your level is not that of a journalist, starting from your appearance…”

The sexist and offensive remarks were denounced by the Association of Journalists of Kosovo, and also by the Association of Sports Journalists, while the Football Federation of Kosovo’s Disciplinary Committee has opened a disciplinary procedure against the coach.

IT WASN’T LONG BEFORE THEY WERE FORCED TO MOVE ON WITH THEIR CRITIQUE TO THE THIRD HIGH PROFILE INCIDENT OF THE WEEK.

But Batatina had already become old news by the following day when the Imam Shefqet Krasniqi decided to share his own views on women. Invited onto one of the most watched evening shows, RTV Dukagjini’s “Debat Plus me Ermal Pandurin,” to talk about solidarity during Ramadan, he instead used the space provided to him to do what sexist and homophobic pundits do best: He fed into the narrative of segregated gender roles and the dominance of a patriarchal order.

“Religion shows everybody their place: Men belong in the oda — the oda is for men. One should make another oda for women,” he suggested. “Men can learn from men and women from women. When they are mixed together, one cannot tell anymore who is a man and who is a woman … a woman goes to war but she cannot fight as a man. A woman has the tools, but she cannot use them as men do.”

Krasniqi faced strong criticism, particularly from various circles. But, in exhaustion, it wasn’t long before they were forced to move on with their critique to the third high profile incident of the week.

While the Imam was talking about how the world needs to exist in a segregated, gendered composition, veteran journalist Baton Haxhiu — who now owns the Albanian Post and is a frequent political analyst in Albania — was doing environmental analysis.

The former director of KLAN TV in Kosovo said that Albania does not have to listen to the calls of foreigners, including Leonardo di Caprio, who have appealed to the government to declare the Vjosa River and its surroundings a “National Park.” Instead, he suggested other actions.

“Find a gorgeous girl for Leonardo di Caprio and offer her to him [on the table], and tell him this is a gift, but do not bring other topics to the table.”

Media reinforcing a patriarchal narrative

The sentences so easily rolled out by Batatina, Krasniqi and Haxhiu form an objectifying and oppressive lense toward women and are exactly the dominant ideas that are reproduced and maintained as standard with the aid of the daily media production.

One has to be a football expert in order to assess the words of the sports journalist, but Batatina didn’t patronize her for her lack of expertise but for her gender, just as Krasniqi does with all women.

Furthermore the hegemonic masculinity of sports and religion traditionally sees women sports journalists, or any women, as unwanted newcomers in the male realm who should have stayed in the kitchen. And the media reproduces exactly that deformed reality within a patriarchal ideology.

How media organizations participate in the culture of oppression is best seen through the immediate reaction — or lack of it — from journalists, editors and media owners toward the sexism by Batatina and Krasniqi. One might expect their comments to instantly backfire, but there was minimal reaction from journalists in the studio, or their superiors.

HAVE YOU EVER STOPPED TO CONSIDER: FROM WHOSE PERSPECTIVE IS THE STORY?

And their action and lack of it sends a message: Here we provide a platform for outright gender discrimination. That galling message is strengthened by media that do not filter hate speech from comments on their websites, helping to stoke the fire of misogynistic scorn aimed at Krelani, the sports journalist, and other women.

Even when gendered jobs and roles are challenged by women themselves, the stereotypes remain and are reinforced in editorial decisions.

Women’s voices, or those of anybody who is not an Albanian, heterosexual man, are widely lacking from core positions in media settings and organizations, which continue to depict public life as a male domain. For example the vast majority of political scientists and commentators are men, while women are more often invited to talk about social issues, health and education that are marginalized from front pages or prime time shows.

Patriarchy dominates the news. Such discrimination against women and their experiences is manifested not only in the use of language, but also in the angle of stories. Have you ever stopped to consider: From whose perspective is the story? Who is included and who is excluded? How many of those I’m seeing or hearing from are women?

Now, with this in mind, let’s look again at Krasniqi’s suggestion that women are not for war. It is hardly the first time we have come across such an assertion in recent years. Since the end of the war in Kosovo, in a media landscape dominated by men, we have continuously replicated Krasniqi’s words with women’s portrayal as passive victims. This excludes them from their agency and contributes to reinforcing the narrative of war and liberation written and led by men.

Gender representation in media reflects a constructed reality that is the result of various thoughts and decisions made by media workers who articulate similar messages to those of Batatina, Krasniqi and Haxhiu.

WHILE THE SCRIPT HAS LONG BECOME OLD, WE CANNOT AFFORD TO SIMPLY TURN THE CHANNEL.

The latter’s comments are particularly deplorable, because as a man who has long held an influential role in the Albanian language media landscape, he sent a public message that institutionalized sexism is here to dominate.

With his casual inference toward sex trafficking, Haxhiu normalized the objectification of women, suggesting that they exist simply to be subordinated and oppressed — but not as agents of social change. It was a stark reminder that we are still a long way from seeing serious discussion of public policies to tackle gender-based violence, discrimination or social injustice in such prime time slots.

But while the script has long become old, we cannot afford to simply turn the channel. The majority of clickbait media may do their best to uphold the patriarchal reality, but until news organizations represent a feminist perspective we must continue to speak out.

This article was originally produced for and published by Kosovo 2.0. It has been re-published here with permission.

Author: Dafina Halili, K2.0 contributing editor, covering mainly human rights and social justice issues. Dafina has a master’s degree in diversity and the media from the University of Westminster in London, U.K..

Photo credit: Arrita Katona / K2.0

“YOUNG&DIVERSE” PODCAST WITH SELMA SELMAN – “I have to serve as a role model and that means that I cannot fail”

April 8, 2021

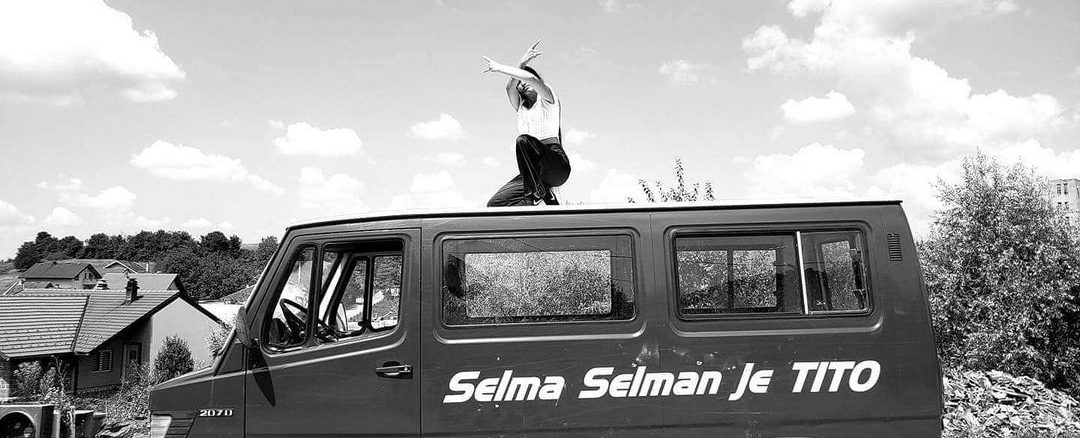

Selma Selman is an artist from Bosnia and Herzegovina. She incorporates her creativity, but also identity aspects into her artwork. Being part of a Roma family that earns their living from collecting and selling iron, Selma uses iron and reusable materials in her art. In her show Mercedes Matrix breaks a Mercedes car with the help of her family in front of an audience in order to question labour and capitalism in Roma settings and beyond. The Selman family wrote “Selma Selman is Tito” – referring to the Yugoslav leader – on their family van to point out the solidarity spirit and power she brings to their village. Selma owns Selma Selman studio in Bosnia and helps young Roma girls to obtain necessary education through her foundation.

Selman says that as a Roma woman she has been targeted by a lot of hate speech. Selman’s approach to combating hate is to ignore it to the point when haters become conscious of their own unhappiness.

This episode of the podcast “Young and Diverse” is created in cooperation with the podcast Celebrate Life and local artist from North Macedonia, Goran Kostovski- Indog. You can listen to the full episode here.

This pandemic has changed the world. Marginalized communities have been ignored. Kids were not able to attend school because of the lack of computers. Recently you made your own studio and with your last project “Get the Hack to School“you did a lot for the local community. Can you tell more about this project?

Thinking about the pandemic makes me think about the situation of Roma people, before and now. And the reality is that Roma people were always in a trouble, even before the pandemic, but now it is even worse. There was never a good situation where Roma people could live normally and with the pandemic it is much worse.

And in regards to that I realised that I have to create something; a cultural institution in my village because such a thing doesn’t exist there. I realised that I am going to open and build my studio as a place where everyone, not restricted to Roma, can come, borrow a book, borrow a laptop, ask for information they need. This is a place that serves for education and emancipation.

Talking about this, my project “Get the Hack to School” which started in 2017 is actually funding firstly girls with full scholarships. The reason why I am targeting girls is because I want all of these girls from my village to have elementary school [education]. This is somethings which I think is a human right for every child and for Roma girls. This foundation is not restricted only to Roma girls. I am also giving scholarships to boys. From 2017 to 2020 we were giving out school lunches, but because of the pandemic we had to stop this because it was not safe.

For now I can say that we did a lot of progress with this small help. (…)For example now we have one girl who enrolled into Law school, one girl is studying art school, 2 boys into high school and all other kids to primary school.

As much as this is beautiful to do at the same time is very hard for me. I have to serve as a [role] model. Being a [role] model means that you cannot fail. It means that you always must show them that education is the right way to have a normal and good life. At the same time you always have to have the trust from those girls that you wish the best to them. Since the Roma people were traumatised by the white people, where the white people were using them whether to get funds or some things from them, Roma people started to assume that even someone who is coming from their own community is also trying to abuse them. This is why this is a big challenge for me to gain the trust. I can say that I really have huge respect for my community and family.

In one interview for the Macedonian feminist festival Prvo pa Zensko (First Born Girl), you state that the Roma are the planet’s leading social, ecological and technological futurists. Roma people have been recycling for many years and earned a living from this, while the Western world only a few years ago started to become aware of recycling plastics as a benefit. How to overcome those narratives in the Balkans in which Roma are just perceived as collectors of plastics for their own survival- but often people miss to see the great ecological contribution they have with this job?

For many years, people who were collecting iron, scrap metal or plastic were perceived as people who were working undervalued labor. It was not interesting 100 years ago to collect this stuff, because people didn’t think about ecology so much. The funny and at the same time beautiful thing is that Roma people were unconscious that they were helping themselves, but also to the world.

You speak in many ways through your art as a Roma woman, you relate to your origins in Bosnia despite being famous worldwide, bringing close connections to how your family lives and works. In your exhibition Mercedes Matrix you question the concepts of labor, survival, economic struggles and daily living of Roma families. Can you elaborate on Mercedes Matrix exhibition?

To be honest my family really loves to participate in my show. They like that they can be paid more. The interesting part for the Mercedes Matrix show in 2019 was that this was the first time I did a public performance with my family.

Mercedes Matrix was the intro into collective performances with my family. They told me that when they do this performances with me it is totally different situation and circumstances in the art world. They said that when they usually do this work at home, breaking cars on a daily basis doesn’t represent anything more than a job that gives you money. And this job does not represent a value. You don’t get any value for this job. You are perceived as an iron picker and nothing else. But when they were transformed into these circumstances in the art world they felt proud of what they do. This was the first time for them that they have been recognized.

You have a picture in your family van that says “Selma Selman is Tito“. What is that about?

People always told me that Tito is not a woman. The fact is that Tito, in the former Yugoslavia, represented someone who had the power- the power to lead the nation. Regardless of the troubles and problems in which Yugoslavia went. I think that Tito represented power and this is what I represent to my village.

For many Balkan countries, the rule of “hate silence“ in the media applies to many community groups including the Roma community. In this case, hate is not expressed through the discourse or reporting, but through ignoring and staying silent. For what problems that concern the Roma community in the Balkans do the media stay silent?

The media has a big role [to play]. Any media, but especially social media. They have to be really conscious of what they do. I know from my personal experience. I get a lot of hate from white people. I am on all social media and all media in Bosnia. People like to interview me. I use the media and interviews in order to say something clever for them. I give interviews to those portals who are read by haters and those who are read by educated people. From those people who read those, I would say, “cheap“ portals and magazines you get a lot of hate. You can see how much time they have to actually share the hate. On one of my interviews I got 300 comments which are all about hate. The hate always existed and stereotypes based on anything. In order to fight that you show them how successful you can be and not react to their stupidity.

It is really easy to hate. Who are those people that decide on what someone else has to do and they instantly hate? Why do people hate?

It is a really great philosophical question. Why [do] people hate? At the same time why people love? It is the same. It is just like yin-yang. The darkness exists in the happiness and the happiness exists in the darkness. We need to find the balance and the balance is the hardest to achieve. People who hated you that means that they are not satisfied with themselves and the only way to feel a little bit happier is if they make you sad. We live in a world where many people are unhappy, because of the government, because of the salaries, because of the money, the law… I cannot even judge these people. The only way how to fight it is to just let it go. Then, they themselves will maybe die in hate or be unhappy all their life.

What would you recommend to the young people in the Balkans?

Maybe I can say something through me, what I have learned through all this experiences with travelling, working, troubles, living in underprivileged circumstances and making myself visible. The only thing which helped to build myself is that I never perceived myself [as being]different as people would call me. I always perceived [myself] normal and equal to others. I never perceived myself as not being able to do something. I always viewed that if I want something I can really do it regardless of how much time it is going to take, but it is going to happen. For me, I don’t believe in the hard work, but in the clever and smart work, making strategy and thinking about what I really want. Once you realize what you really want, you will realize that being proud on your national identity doesn’t make sense. Being proud of your country doesn’t make sense. Country is an invented terminology. I think that the only tactic for me to succeed is this normalization, that I am normal, no smarter than other, not more stupid than other, just me.

All of us who were born underprivileged, we all went through similar experiences of discrimination. The facts is that these forms of discrimination still exist today.

The only way to fight haters is [not feeling pity for] yourself and not showing them how vulnerable you are. It is the hardest thing to do. How do you stay calm when someone is bullying you? I didn’t have a lot of friends in elementary school. Even though I was white, I was still perceived as dirty and black in the school. Then I realized when I was getting the best grades, people started to perceive me as normal. This was my strategy.

Editor’s note: This is an edited version of Selma Selman’s interview. You can listen to the whole interview on Spotify’s Ancor. Some parts were edited for more clarity.

Photo credit: Selma Selman Instagram Profile

Monthly Monitoring Highlight: Ethnic hate speech and narratives of divide

April 6, 2021

Throughout March, Reporting Diversity Network monitoring team has detected several incidents related to xenophobia and hate speech based on ethnicity in the Western Balkan media. Hate speech was spread by politicians, influential figures, and other public figures. While there is a consistency in spreading hateful rhetoric targeting migrants and refugees, media representation of the Roma community does not exist, which is known as “hate silence“.

Genocide denial by Montenegro Minister of Justice

The Minister of Justice in Montenegro, Vladimir Leposavic, indirectly denied the genocide in Srebrenica by challenging the legitimacy of the Hague Tribunal, which recognised it as a genocide. “I am ready to admit that the crime of genocide was committed in Srebrenica when it is unequivocally established”, he said. According to Leposavic, the Hague Tribunal has lost its credibility. Leposavic specifically said:

“The Hague tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, in addition to being established by a resolution instead of an international treaty, almost completely lost its legitimacy when it was established that the evidence of the Council of Europe rapporteur on the extraction and trafficking of organs of Serb civilian victims in Kosovo was destroyed in that court.”

The US Embassy in Montenegro, but also domestic representatives of political parties, CSOs and activists urged the government to hold Leposavic accountable for his words. Emir Suljagic, Director of Srebrenica Memorial Center warned of the possible ethnic intolerance and violence inspired by such rhetoric. He tweeted: “With this government in Montenegro, I cannot exclude organised violence towards Bosnians in Montenegro in the near future. To start with, through ‘paramilitary’ formations. The signal for violence will come from the country”.

Montenegrin Prime Minister Zdravko Krivokapić, however, stated that the government respects the Declaration of Acceptance of the European Parliament resolution adopted by the Parliament of Montenegro in 2009, which condemns the genocide in Srebrenica committed in 1995, and all other war crimes committed during the conflict in the former Yugoslavia.

Part of the public in Montenegro urged Minister Leposavic to resign due to his statements, which he did not do.

Mixed ethnic marriages to discredit political opponents in the political scene in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Faruk Kapidzic, former Minister at Sarajevo Canton Government and current Chairman of the National Commission for Monuments, posted a Facebook status in which he aimed to discredit deputy mayor candidate, Ivana Maric. He accused the voters of the opponent parties as responsible for voting Maric. He described all voters as naive.

“Naive believers and members of the Islamic Community, as well as new businessmen who voted for People and Justice (political party), are also to blame for that. And everyone from working class and mixed marriages and supporters of socialist and realist ideologies who voted for the SDP (political party) are also to blame.“

Kapidzic shared the status on his Facebook profile, but many media outlets shared the status. He was afterwards invited in several media to explain himself why mixed marriages were mentioned in his Facebook status on which he answered that the does not understand why the media found that problematic as he listed all voters.

Ethnicity in ethnically mixed Bosnia and Herzegovina, and ethnically mixed marriages in particular, are a very sensitive topic. This is not something that should be utilised in political purposes and risk adding to an existing divides in the society.

Racist coverage of COVID-19 in Albanian media

Four websites in Albania published a segment of a video that labels COVID-19 as a Chinese virus which brought a lot of hateful comments on the Internet. Articles show a short video with an old patient in hospital who is sharing his experience of hisCOVID-19 battle in an interview. Instead of showing the entire interview, the portals included only the 12-seconds video segment where the racial hate speech is articulated. Headlines on the portals included this one: “Hospital patient Shefqet Ndroqi, shares his battle with COVID-19: “I prefer dying from God rather than those sons of a bitch – the Chinese”.

Clickbait headlines and mal-intended usage of video interview in this case is very problematic as it is targeting Chinese people (since the virus originated in China) rather than warning of the possible consequences of COVID-19 and the need to respect preventive measures. It also influences public discussion, as evidenced in the readers’ comments, without bringing the needed benefit – care for public health.

Nationalist narratives in a popular Serbian TV talk show

Reporting Diversity Network selected Ivan Ivanovic, host of the TV talk show “Evening with Ivan Ivanovic“ as the Balkan Troll of the Month. Ivanovic used his episode 593 as a space to spread nationalist narratives by calling Podgorica, the capital of Montenegro, a Serbian village. Later during the show, he made a sexist comment about women from Montenegrin town Ulcinj.

RDN members, Media Diversity Institute Western Balkans and Center for Investigative Journalism-Montenegro jointly expressed their concerns on the rise of nationalism in Serbian and Montenegrin media. In addition politicians in those two countries, where nationalism is present in the daily life, are creating this atmosphere. At the same time narratives of division, that are fed by nationalism, are very present in the media of both Serbia and Montenegro. Jovana Marovic from Politikon Network and Nikola Burazer from European Western Balkans warn of the rise of nationalism in both countries and that those nationalist narratives complement and strengthen each other. This has a potential to negatively influence good neighborly relations in the Balkans.

Xenophobia and anti-migrant narratives

Xenophobia and narratives that are targeting migrants and refugees are present across the Western Balkans and throughout March, RDN monitoring uncovered problematic narratives in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia. These narratives, that predominantly represent refugees and migrants as a security threat, appear in traditional media as well as on social media.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the antimigrant.ba portal, which was RDN 2.0 February Troll, continues to spread anti-migrant feelings with headlines such as “Take migrant intruders to your countries, don’t feed them in ours”.

In Albania, migrants are depicted as a threat to society. “Stop the migrants that are threatening Albanian families” is just one of the anti-migrant messages in the media.

YouTube and other social media can be a source of problematic discourse about ‘the other’. That is the case in Serbia where the leader of Narodna Patrola (People Patrole), an informal group that is ‘protecting’ people from migrants, gave an interview to the YouTube channel ‘Mario zna’ (Mario knows). In the interview he claimed that some countries have ” “intentionally released prisoners into the migrant crisis” and that “(migrants) are an organised army that came to cause destabilization”.

Many other misleading and unfounded statements were part of the YouTube video which, at the time of the writing, had over 22 thousand views and obvious potential to influence opinion and attitudes of citizens towards the migrant and refugee community.

“Hate silence”

While media outlets give an open platform for spreading divisive narratives, there seems to be no space for the problems of local members of the Roma community. Despite of Roma being large ethnic minority across the Balkans they are rarely portrayed in the media.

RDN members call this hate silence, as in this case, hate is not expressed through the discourse or portrayal, but through ignoring and staying silent. MDI has already raised issue around lack of media discussion on discrimination of Roma people in the media in Serbia, however, the situation is relatively similar in other Western Balkan countries as well.

Reporting Diversity Network 2.0 stresses that the media landscape should be free from the narratives of ethnic divide. Furthermore, we urge the media outlets, journalists and media representatives to break the “hate silence“ for certain ethnic minorities such as the Roma community and contribute towards more frequent and accurate representation of life and challenges of Roma people.

BALKAN TROLL OF THE MONTH: Ivan Ivanovic, a TV Host from Serbia

March 31, 2021

The Balkan Troll of the Month is an individual, a group of individuals or a media outlet that spreads hate on the internet based on gender, ethnicity, religion, or other diversity categories. The Balkan Troll is selected based on hate speech incidents identified across the Western Balkans region.

Our March Troll is Ivan Ivanovic, a TV host from Serbia. Ivan Ivanovic hosts the show ‘Evening with Ivan Ivanovic’ which is one of the most popular TV shows in the country. In episode 593, RDN monitors detected nationalist and sexist narratives towards Montenegrins. The episode was aired on 26 February 2021 on the TV stations Nova S, Nova BH and afterwards published on the TV show’s own Youtube channel. At the time of the writing the episode has a little less than 100,000 views on YouTube only.

In his show, Ivan Ivanovic called Podgorica a Serbian village. Ivanovic joked by saying “Serbian villages have a future. For example, Podgorica.” In the second part of his joke he attempted to explain his joke due to a word play in the Serbian language and he said that he meant the football team Buducnost (translated: future) from Podgorica. Ivanovic ended his joke only by saying “I am kidding. Greetings to our brothers in Podgorica“.

Ivanovic’s statement is offensive for Montenegro and its citizens as it denies the identity of people of Montenegro, their state and nation, by calling them Serbian and furthermore naming their capital “a village”.

Later during the show, Ivanovic made a joke about women from the Montenegrin town, Ulcinj. He referred to a Danish girl named Eldina who grows her mustache and eyebrows so that men would stop constantly flirting with her. Having said that, he added, “Apparently, she’s never been to Ulcinj”. This commentary is an obvious sexist remark, directed towards Montenegrin women.

This is not the first time Ivanovic has made problematic statements that were not welcomed by part of his audience. In 2014, one of the jokes he made was about underage rape victims in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Although he issued an apology in the next episode, this remains a proof that humor in the media requires a lot of thinking and professional and ethical approach. Despite his explanation that he, by no means, had bad intentions, many of his jokes, aired on TV with national coverage, and framed as ‘harmless’ humor, have been bordering with sexism and other types of stereotypes as well as usage of terminology that cannot be considered politically correct.

Humour as a dangerous zone where hateful narratives are widely spread

While humour is welcomed on television talk shows as a powerful tool, the above-mentioned examples are neither humourous nor part of a stand-up comedy performance. Such narratives can be considered offensive, and Ivan Ivanovic gave them a platform and visibility through his very popular TV show. This type of humor does not transform or deconstruct some of the omnipresent divisive narratives in the Balkans, instead, it further perpetuates conflicts in the Balkans and brings those narratives closer to younger generations and those who should be detached from divisions.

Many bloggers and media figures successfully use humor and satire as part of tackling some of the global problems that the world is facing. However, there is one important question: is the price of making someone laugh worth using humor that is targeting ‘the other’? By other we mean either a group in the society (such as jokes about ‘Cige’ as Ivanovic calls Roma people in some of his jokes) or in the Western Balkan neighborhood (like Montenegro in this case).

Rise of nationalist narratives in Montenegro and Serbia

RDN monitors have detected several incidents related to nationalist narratives in the media in both countries. Many of these examples from both Serbian and Montenegrin media are denying the existence of Montenegro as a state and nation. These narratives are spread by politicians and influential figures as well as media.

“Nationalism in both countries is equally important. They influence and strengthen each other. This is a result of the politics by the political parties that works in their own interests. When they cannot offer sustainable policies and sustainable solutions, they (political parties) still play on the identity card, which is highly problematic”- says Jovana Marovic from Politikon Network. Marovic and Nikola Burazer from European Western Balkans elaborate more on the nationalist discourses in Serbian and Montenegrin society in the video interview made by RDN 2.0 members Media Diversity Institute Western Balkans and Center for Investigative Journalism- Montenegro. The video is available in local languages.

If you want to learn more about how media should report on ethnicity, read more in the “Getting the Facts Right: Reporting Ethnicity and Religion“ case study. The case study and other useful resources are available on RDN website resources page.